Tide and Time

Coastal defences have been constructed in Britain since Roman times, to protect human settlements from the onslaught of high seas and relentless rolling waves.

However, it is now increasingly recognised that these defences are economically unsustainable. The Government’s policy change from its previous ‘Hold-the line’ stance, in which defences were to be maintained and land protected, to a new ‘Managed realignment‘ policy that lets Coastal erosion take its natural course. As a result this has left people living on the edge of Britain with little choice but to abandon their homes or await the inevitable. This project documents the places, and people that live at the mercy of Mother nature.

“Like many major natural disasters that remain fixed in personal and national psyches, nobody saw the 1953 floods coming. With no warning whatsoever, wild gales brought roaring waters down the North Sea and crashed them over land into houses” - Extract from Professor Jules Pretty's book 'The Luminous Coast'

Mrs Boggis gazes out her sea facing window in Easter Bavents, Suffolk. Deprived of fresh supplies of sediment drifting down from the north, the cliffs of Easton Bavents erode fast. At the base, waves launched a devastating offensive, whipped up by the North Sea’s notorious winds, while at the top of the cliffs Suffolk’s soft, spongey clay proved helpless in the face of percolating rainfall.

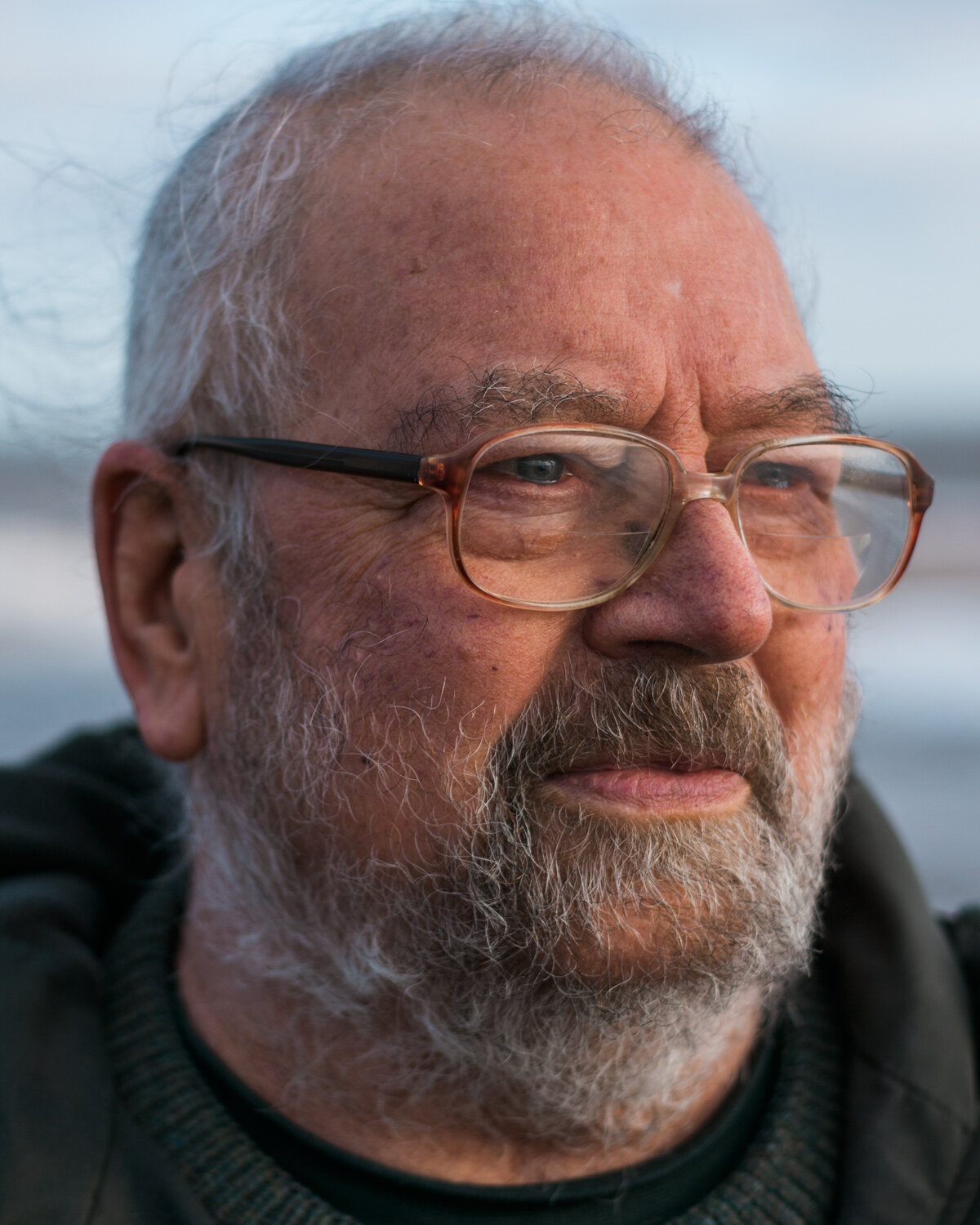

Resident Peter Boggis. After witnessing the instalment of defences at Kessingland, Peter is adamant that the sea walls have had an adverse effect on on Easton Bavents: "For months a drag line was based at their harbour, digging out the stone which came from our beach and cliffs and which was blocking the passage.”

The view from an abandoned house in Eastern Bavents, Suffolk. While defence works at the larger, more popular seaside resorts continues apace, this tiny community’s increasingly desperate demands for protection go unheeded by the authorities.

A house in Dunwich peaks over the eroded cliff. In the 11th century Dunwich was the tenth largest port in the British Isles; a crusader port, a naval base, and a religious centre with many large churches, monasteries, hospitals, grand public buildings. It had one sixth of the population of London and two seats in Parliament. Today the village has a population of just 120.

A mere 450,000 years ago the land groaned under an ice sheet perhaps half a mile thick. Each period has left a temporary legacy in the rocks of Suffolk: a wealth of sands, gravels, silts, clays and limestones.

Steve Aldous has lived in Dunwich all his life (on and off). "Since the tidal serge in 2007, we haven't seen too much damage. They've put in some temporary protection and so far it seems to be working."

The view from Steve's bedroom.

The view from Jaywick martello tower. In 1953 Jaywick, like the rest of the east coast, was hit by the largest tidal surge in modern times. The flood claimed the lives of 35 people and decimated the entire village.

A resident of Jaywick in Essex. Still to this day the village was never rebuilt such is the probability of repeat flooding. Jaywick was assessed as the countries most deprived community in 2015.

After the flood's of Jaywick in 53' the government at the time invested heavily in sea defences. However the walls were built facing the sea, even though the 53' flood water had crept up the river Colne and spilled into the back of the village. Not only has this ruined the view of the sea but more devastatingly, it has created a bowl effect, keeping flood water in, rather than letting it run back into the sea.

Jaywick's prefab houses are all only one storey high. The roofs comically appear to be peeking over the wall.

The prevailing wind sweeps the sand North, piling it up on the defences, Jaywick.

A van parked in Jaywick.

Happisburgh, Norfolk, is one of the hardest hit communities on the east coast. The government has relocated nearly all the residents from the sea front houses. In this picture Bryony Nierop-Reading, one of the only few remaining residents, mows the lawn of the bungalow she refuses to leave. "Why should I be made to move from the home I love? I think it would be totally immoral for me to take any money at all for it."

Bryony in her home that she bought in 2008; believing at the time that sea defences would be kept up and her house would be safe for a number of years.

A storm brews in Bryony's back garden, half of which has been lost to the sea.

Bryony's cat shelters from the pouring rain. An increase in tidal surges has meant that the cliff edge is now creeping towards the house at a faster rate than expected.

In 2007 4,000 tonnes of rocks were placed at the foot of the cliffs in Happisburgh. At a cost of £200,000 to North Norfolk District Council and £50,000 to villagers but these defences have now been washed away, leading to huge erosion.

A big tidal surge in 2013 finally undermined Bryony's bungalow. She was forced to move across the street and into a caravan with all her possessions. "At the age of 70 I've lost my house and now I'm on the verge of losing everything. I'm fighting to keep my life together." - Photograph taken in 2017.

The old sea defences are no match for the tidal surges experienced in this part of the UK.

Sea foam residue left by the waves.

Tony & Yvonne King also lost their home in Bacton, Norfolk, to the tidal surge of 2013.

Road to nowhere. Not surprisingly, the common perception of people in this part of Norfolk seems to be one of abandonment—of bureaucrats ensconced in the warm and dry of Whitehall, fiddling while communities flood. People know they can’t stop the sea. They know that living with the threat of storms and surges is part and parcel of choosing to lay your hat on the most dynamic coastline in Europe.

A holiday home park is battered by the prevailing easterly wind in West Sussex. The park has already had to move a significant amount of the homes back from the edge of the cliff.

The view from below the cliffs. Although much of Sussex's geological mass is made up chalk. There are many vulnerable sections that are mud, lime and sandstone. The coastal stretch from Eastbourne to Portsmouth is at particular risk due to long shore drift and constant north-easterly winds.

A Norfolk home creeps ever nearer to the edge.

An abandoned boarded up static home is left on the cliffside in Sussex.

A First World War bunker illustrates just how far the coast has eroded in the last 100 years.

The limestone cliffs of the South and East coasts of the UK are soft enough to carve into with a piece of flint.

The onset of global warming and potential rises in sea levels mean the future for Britons coast is unpredictable. But one thing is for sure is that the governments new policies that come into effect in various areas come from now until 2020, will mean British coastlines will be dramatically altered in years to come.

The remains of Tony & Yvonne's home.

The last remaining railing of the steps that used to lead down to the beach near Hopton, Suffolk, memorialised with plastic flowers.